[School of Global Japanese Studies](Kishi Seminar)ABR Collaborative Practice with Istanbul University, Turkey: International Collaborative Learning: Reexamining “Multicultural Coexistence” Through Art

Jan. 13, 2026

In September 2025, the Kishi Seminar conducted an international collaborative practice using Arts-Based Research (ABR) with students from Istanbul University in Turkey. The theme was “Multicultural Coexistence.” This initiative involved encountering others from different cultural backgrounds and experiencing shared daily life from “alternative perspectives,” prompting students to reexamine their own viewpoints and values while opening new possibilities of “it could be like this.”

Japanese and Turkish students paired up, walked the city streets, took photographs, and engaged in dialogue. What emerged was not learning focused on finding correct answers, but learning where questions continually arose.

Below are the process and insights from this practice through the students' own words.

Photo: In front of Istanbul University's main gate

■The beginning ABR experience: Understanding others through body, photo, and narrative (Ayane NANJYO)

On the first day, we conducted multiple workshops aimed at introducing Istanbul University students to ABR. These included self-introductions using physical expression, mapping, understanding others through narrative expression, and cultural exploration using photographs. This day served as both an icebreaker and an introduction to ABR.

During the opening exercise, where participants expressed their names through movement, Some students initially seemed hesitant. However, as the activity progressed, their tensions eased, and by the end, laughter filled the room as everyone opened up. This relaxed appearance allowed the subsequent activities to proceed smoothly.

For the photo activity, students selected one image capturing Japanese daily life that resonated with the concept of “multicultural coexistence.” Explaining their choices naturally revealed each person's values and worldview.

While this activity also prepared them for the walking ethnography starting the next day, it already highlighted perspectives vastly different from our own. These differences were fascinating and heightened anticipation for the upcoming exploration.

Photo: Participants sharing why they chose their selected photos

■What can we see through walking: Practicing of walking ethnography (Hinata HANASAKI)

Japanese and Turkish students paired up to conduct walking ethnography at Meiji University and Istanbul University, respectively, using themes such as gender, multicultural coexistence, place memory, well-being, and emotions (people's feelings) as their guides.

Walking ethnography is a method of exploring “the culture and activities of a place” by observing people and scenery while walking through the city, using photographs and notes. Walking allows one to pause at events and scenes often overlooked, and through photographs and dialogue, the differences between “one's own perspective” and “the other's perspective” gradually emerge.

I walked the city with the theme of “multicultural coexistence.” My first stop was the historic Takushimu Square area, a place where people have gathered for centuries. Later, I took a ferry from the European side of Turkey to the Asian side (Anatolia), experiencing the starkly different cityscapes within the same metropolis.

As we walked, whenever I asked, “What's that?” the Turkish students would respond, “Isn't that in Japan?” Through these exchanges, we could naturally share landscapes and customs that we each took for granted in our own countries.

Along the way, we encountered a demonstration advocating for animal rights, and the Turkish students told me about Turkey's political situation. Learning that many students held their own opinions about society and politics struck me as a stark contrast to Japan.

These insights weren't something I could have gained just by reading materials or listening to lectures in a classroom. Looking back now, I feel this learning came precisely because we walked the streets together, stood in the same places, and engaged in repeated dialogue.

Photo: A scene photographed with the theme of “Multicultural Coexistence”

Photo: A demonstration advocating for animal rights

■From photographs to poetry: Understanding others through imagination (Shieru TSUCHIYA)

The next day, in a classroom at Istanbul University, we each brought photographs we had taken. Here, we engaged in a slightly unique ABR practice. First, we exchanged photographs with a partner, showing them without explaining “why we took this photo.” What emerged from this was surprise and questions like, “Why did you choose this photo?”

In the next step, we attempted to imagine the reasons behind the other person's photo from their perspective and express it poetically. In other words, we sought to explore the other's experience not through ‘explanation,’ but through ‘imagination’ and ‘poetry.’ Using the photo as a clue, we imagined what reality the other person saw and what feelings they must have had standing in that place. Then, by reweaving this not into words but into poetry, our understanding of their culture and experience deepened further.

Our pair walked the city with the theme “Memories of Place” and took photos. When selecting five photos each to write poems about, we recalled not just the information visible in the photos, but also what we had talked about when visiting those places together, and the expressions on each other's faces at the time. Looking back now, I feel it was less about simply thinking from the other's perspective and more like reconstructing memories, fitting puzzle pieces together.

During our walk, we visited the Istanbul Archaeology Museum. There, we saw many historical artifacts. For me, it was moving to see things I'd only heard about in textbooks right on my front.

But while writing the poem, I realized that for my partner, Serkan, the history and culture embodied in those exhibits felt much more familiar than they did to me. It was precisely because this was a work about writing poetry from the other's perspective that I could recognize this difference in viewpoint anew.

What struck me most strongly through this work was how differences in perception can become a force that opens dialogue. Rather than denying these differences, accepting them with a “Yes, and” approach drew out even the most difficult-to-articulate emotions and values. In typical communication, differences within a dialogue are often perceived negatively. However, during this exercise, even when the poems we wrote differed from what we originally intended, we didn't negate them. Instead, an unconscious “Yes, and” communication naturally emerged. In fact, I felt that it was precisely because of these differences that we were able to think more deeply and draw out things that are difficult to put into words, like the emotions we carry or the values we hold dear.

Photo: Reading the poems we created aloud

■Reading Poetry ——Same Photo, Different Memories (Mihoko MOTOYOSHI)

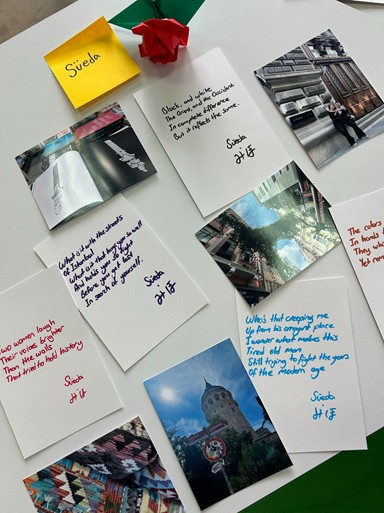

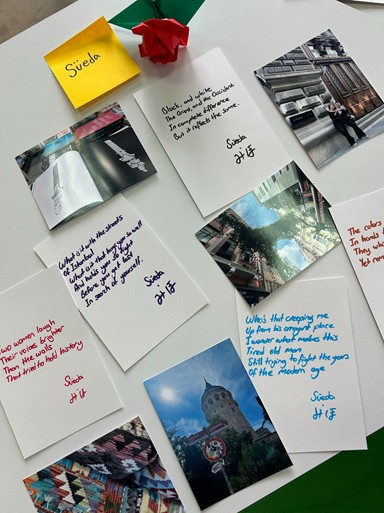

Finally, we had time for pairs to read each other's poems aloud. My partner, Süeda, chose a photo I took of a carpet and wrote a poem based on it.

The reason I took this photo was that my conversation with Süeda about “Kawaii,” a key aspect of Japanese youth culture, had left a strong impression on me. For me, born and raised in Japan, the sense of “kawaii” is deeply familiar, and I naturally found that feeling within the colorful, pop-style carpet.

“Cute,” “pretty,” “beautiful,” “unique.”

English has many adjectives, but I feel Japan's unique sense of “kawaii” doesn't fully fit any of them. Walking through the Turkish city together that day, discussing and sharing those subtle nuances with Süeda left a strong impression on me. That's precisely why I photographed the rug I found most “kawaii” that day.

Yet, the meaning Süeda sensed from that rug photo and poured into her poem differed from my own perception. While that rug symbolized “kawaii” for me, for her it evoked memories of home. She explained that its design had roots in the traditional patterns of the region where she was born and raised.

As I listened to her story, I found myself recalling my own memories of growing up in Japan, surrounded by “cute things.” Perhaps, I thought, my own “kawaii” culture was also, unconsciously, a cherished part of my memories, tied to my hometown and the environment where I grew up.

Finding shared emotions and thoughts through a single photograph with Süeda, despite our different birthplaces and cultures, was a profoundly unforgettable experience.

This dialogue through photographs and poetry felt less about comparing differences and more like a quiet time, touching upon each other's memories and values.

Photo: A photograph I took

Photo: A poem Süeda created using my photograph

■Reflecting on the Whole Experience (Kawa TOKUNAGA)

I spent time with Istanbul University students right up until my final day back home. Though we grew up in different environments, every conversation brought countless surprises. The more we talked, the more I wanted to know and ask about. I'm truly grateful for their attitude—they consistently faced my questions with sincerity and kept answering them. But it's not just them—my fondest memories of Turkey are the people. They'd smile back when our eyes met on the street, offer help immediately if I seemed lost, or cheerfully exclaim, “We love Japan!” They were incredibly warm. There's a Turkish proverb: “Bir fincan kahvenin kırk yıl hatırı vardır.” Literally translated as “A cup of coffee has forty years of memory,” it means “Even the smallest act of kindness shown in friendship is never forgotten.” Just like this proverb, the kindness and brightness given to me by so many people in Turkey remain deeply ingrained within me. Turkey is a country that's a bit rough around the edges and far from perfect, but it's warm. I hope to visit again to see those sights and meet those people.

Photo: Meiji University and Istanbul University ABR Practice Team

Finally, I would like to express my heartfelt gratitude to Professor Tuncer Can of Istanbul University, and to Beyza, Dilara, Şamil, Serkan, üeda, Sema, İlayda.

≪Japanese version≫

Japanese and Turkish students paired up, walked the city streets, took photographs, and engaged in dialogue. What emerged was not learning focused on finding correct answers, but learning where questions continually arose.

Below are the process and insights from this practice through the students' own words.

Photo: In front of Istanbul University's main gate

■The beginning ABR experience: Understanding others through body, photo, and narrative (Ayane NANJYO)

On the first day, we conducted multiple workshops aimed at introducing Istanbul University students to ABR. These included self-introductions using physical expression, mapping, understanding others through narrative expression, and cultural exploration using photographs. This day served as both an icebreaker and an introduction to ABR.

During the opening exercise, where participants expressed their names through movement, Some students initially seemed hesitant. However, as the activity progressed, their tensions eased, and by the end, laughter filled the room as everyone opened up. This relaxed appearance allowed the subsequent activities to proceed smoothly.

For the photo activity, students selected one image capturing Japanese daily life that resonated with the concept of “multicultural coexistence.” Explaining their choices naturally revealed each person's values and worldview.

While this activity also prepared them for the walking ethnography starting the next day, it already highlighted perspectives vastly different from our own. These differences were fascinating and heightened anticipation for the upcoming exploration.

Photo: Participants sharing why they chose their selected photos

■What can we see through walking: Practicing of walking ethnography (Hinata HANASAKI)

Japanese and Turkish students paired up to conduct walking ethnography at Meiji University and Istanbul University, respectively, using themes such as gender, multicultural coexistence, place memory, well-being, and emotions (people's feelings) as their guides.

Walking ethnography is a method of exploring “the culture and activities of a place” by observing people and scenery while walking through the city, using photographs and notes. Walking allows one to pause at events and scenes often overlooked, and through photographs and dialogue, the differences between “one's own perspective” and “the other's perspective” gradually emerge.

I walked the city with the theme of “multicultural coexistence.” My first stop was the historic Takushimu Square area, a place where people have gathered for centuries. Later, I took a ferry from the European side of Turkey to the Asian side (Anatolia), experiencing the starkly different cityscapes within the same metropolis.

As we walked, whenever I asked, “What's that?” the Turkish students would respond, “Isn't that in Japan?” Through these exchanges, we could naturally share landscapes and customs that we each took for granted in our own countries.

Along the way, we encountered a demonstration advocating for animal rights, and the Turkish students told me about Turkey's political situation. Learning that many students held their own opinions about society and politics struck me as a stark contrast to Japan.

These insights weren't something I could have gained just by reading materials or listening to lectures in a classroom. Looking back now, I feel this learning came precisely because we walked the streets together, stood in the same places, and engaged in repeated dialogue.

Photo: A scene photographed with the theme of “Multicultural Coexistence”

Photo: A demonstration advocating for animal rights

■From photographs to poetry: Understanding others through imagination (Shieru TSUCHIYA)

The next day, in a classroom at Istanbul University, we each brought photographs we had taken. Here, we engaged in a slightly unique ABR practice. First, we exchanged photographs with a partner, showing them without explaining “why we took this photo.” What emerged from this was surprise and questions like, “Why did you choose this photo?”

In the next step, we attempted to imagine the reasons behind the other person's photo from their perspective and express it poetically. In other words, we sought to explore the other's experience not through ‘explanation,’ but through ‘imagination’ and ‘poetry.’ Using the photo as a clue, we imagined what reality the other person saw and what feelings they must have had standing in that place. Then, by reweaving this not into words but into poetry, our understanding of their culture and experience deepened further.

Our pair walked the city with the theme “Memories of Place” and took photos. When selecting five photos each to write poems about, we recalled not just the information visible in the photos, but also what we had talked about when visiting those places together, and the expressions on each other's faces at the time. Looking back now, I feel it was less about simply thinking from the other's perspective and more like reconstructing memories, fitting puzzle pieces together.

During our walk, we visited the Istanbul Archaeology Museum. There, we saw many historical artifacts. For me, it was moving to see things I'd only heard about in textbooks right on my front.

But while writing the poem, I realized that for my partner, Serkan, the history and culture embodied in those exhibits felt much more familiar than they did to me. It was precisely because this was a work about writing poetry from the other's perspective that I could recognize this difference in viewpoint anew.

What struck me most strongly through this work was how differences in perception can become a force that opens dialogue. Rather than denying these differences, accepting them with a “Yes, and” approach drew out even the most difficult-to-articulate emotions and values. In typical communication, differences within a dialogue are often perceived negatively. However, during this exercise, even when the poems we wrote differed from what we originally intended, we didn't negate them. Instead, an unconscious “Yes, and” communication naturally emerged. In fact, I felt that it was precisely because of these differences that we were able to think more deeply and draw out things that are difficult to put into words, like the emotions we carry or the values we hold dear.

Photo: Reading the poems we created aloud

■Reading Poetry ——Same Photo, Different Memories (Mihoko MOTOYOSHI)

Finally, we had time for pairs to read each other's poems aloud. My partner, Süeda, chose a photo I took of a carpet and wrote a poem based on it.

The reason I took this photo was that my conversation with Süeda about “Kawaii,” a key aspect of Japanese youth culture, had left a strong impression on me. For me, born and raised in Japan, the sense of “kawaii” is deeply familiar, and I naturally found that feeling within the colorful, pop-style carpet.

“Cute,” “pretty,” “beautiful,” “unique.”

English has many adjectives, but I feel Japan's unique sense of “kawaii” doesn't fully fit any of them. Walking through the Turkish city together that day, discussing and sharing those subtle nuances with Süeda left a strong impression on me. That's precisely why I photographed the rug I found most “kawaii” that day.

Yet, the meaning Süeda sensed from that rug photo and poured into her poem differed from my own perception. While that rug symbolized “kawaii” for me, for her it evoked memories of home. She explained that its design had roots in the traditional patterns of the region where she was born and raised.

As I listened to her story, I found myself recalling my own memories of growing up in Japan, surrounded by “cute things.” Perhaps, I thought, my own “kawaii” culture was also, unconsciously, a cherished part of my memories, tied to my hometown and the environment where I grew up.

Finding shared emotions and thoughts through a single photograph with Süeda, despite our different birthplaces and cultures, was a profoundly unforgettable experience.

This dialogue through photographs and poetry felt less about comparing differences and more like a quiet time, touching upon each other's memories and values.

Photo: A photograph I took

Photo: A poem Süeda created using my photograph

■Reflecting on the Whole Experience (Kawa TOKUNAGA)

I spent time with Istanbul University students right up until my final day back home. Though we grew up in different environments, every conversation brought countless surprises. The more we talked, the more I wanted to know and ask about. I'm truly grateful for their attitude—they consistently faced my questions with sincerity and kept answering them. But it's not just them—my fondest memories of Turkey are the people. They'd smile back when our eyes met on the street, offer help immediately if I seemed lost, or cheerfully exclaim, “We love Japan!” They were incredibly warm. There's a Turkish proverb: “Bir fincan kahvenin kırk yıl hatırı vardır.” Literally translated as “A cup of coffee has forty years of memory,” it means “Even the smallest act of kindness shown in friendship is never forgotten.” Just like this proverb, the kindness and brightness given to me by so many people in Turkey remain deeply ingrained within me. Turkey is a country that's a bit rough around the edges and far from perfect, but it's warm. I hope to visit again to see those sights and meet those people.

Photo: Meiji University and Istanbul University ABR Practice Team

Finally, I would like to express my heartfelt gratitude to Professor Tuncer Can of Istanbul University, and to Beyza, Dilara, Şamil, Serkan, üeda, Sema, İlayda.

≪Japanese version≫